May 6, 2024

Problematic Construction Contract Clauses: Weather

This is the tenth blog post in a series that discusses clauses in construction contracts with the goal of providing awareness of contract terms that often cause difficulties and give rise to claims.

Previous blog posts have addressed problematic contract clauses involving differing site conditions, no damages for delay, changes, coordination, suspension of work, warranty and defects liability, variation in quantity, inspection, force majeure, flow down, and compensation and payment. This post discusses weather clauses, and other posts will discuss escalation and oral modifications clauses.

Weather Clauses

Certain contracts have clauses stating that the schedule will not be adjusted for inclement weather at the project site. An example contract states the following:

The Scheduled Mechanical Completion Date will not be extended due to inclement weather conditions which are normal to the general locality of the work site as evidenced by the 20-year average climatic data recorded by the local or national weather bureau or stations. Time for performance of this Agreement includes an allowance for calendar days which, according to historical data, may not be suitable for construction work. It is the Contractor’s responsibility to protect the work site from inclement weather to avoid delays, rework, or inefficient Work.

What is abnormal or unusually severe weather? One approach is to define unusual weather conditions as conditions that prevent construction activities from being performed in a safe, productive manner. However, unsafe weather conditions may not be unusual for the project location. For example, heavy rain is not uncommon in most non-desert areas of the world.

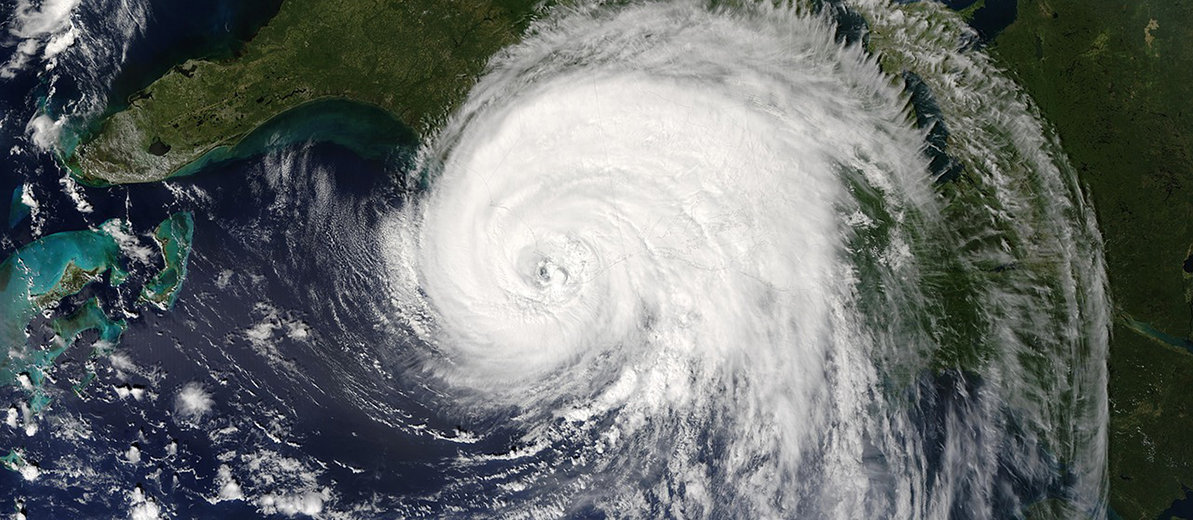

Disputes often arise over time extensions for unusually severe weather. Unusually severe weather is normally classified as an act of God. This cause of delay is separately classified due to the frequency with which contractors cite it as a cause for excusable delay. All types of weather conditions may impact a contractor’s performance: rain,1 the rainy season,2 abnormal humidity,3 frozen earth,4 winter weather,5 extreme heat and summer weather,6 and typhoons.7 Generally, weather for a particular location and time of year can be characterized as falling into one of three categories—ideal, normal, and unusually severe—with the last category being the only basis for excusable delay.

The contract could define unusually severe weather conditions as conditions that exceed the 10-year average minimum or maximum condition (temperature, rain, snow, hail, sleet, wind, etc.) as established by the Weather Bureau for the area where the project is located. The typical remedy for unusually severe weather delays is time but no money.

If the weather complained of is not unusually severe for the particular time and place, and the contractor should have reasonably anticipated these conditions, the owner may argue that there is no justification for relief. Accordingly, if a contractor is working in an area where there is predictably one hurricane a year (as compiled in the U.S. Weather Bureau records or weather records of the foreign geographic location), the contractor may not be entitled to an extension of time for unusually severe weather resulting from a hurricane. However, if there are four hurricanes in this area in the one-year period, the contractor should be entitled to relief.

In seeking time extensions for weather, the contractor must not only show the occurrence of unusually severe weather, but it must also show the type of work being performed and the effect of the weather on the work. Therefore, to obtain a time extension under the unusually severe weather standard, the weather conditions must be more than just inclement.8 The trier of fact will consider the time of year or season, as well as the project location.9 In addition, the standard has a foreseeability element—unless the weather conditions are unusually severe, they are deemed to be foreseeable.10 For example, when a contractor proved delay of 34 days due to rainfall, which was double the average for the same period over the preceding 10 years, half the delay was excused. The other 17 days of delay were the result of normal weather conditions and could be foreseen.11

The type of work being performed is also a consideration in determining if unusually severe weather conditions affected progress. In the early outdoor activities of construction, obviously most susceptible to weather-related problems, weather conditions can seriously affect the entire project schedule. If indoor work is not hampered and can still progress, delay would not be considered for the entire project schedule but only for those activities for which weather is the proximate cause of delay and if those affected activities are on the critical path of the project when the unusually severe weather occurred.

The delay does not have to be a substantial amount of time or involve a string of consecutive days for each day to be considered. To establish actual delay, there must be a showing of the specific work delayed and the extent to which the unusually severe weather conditions prevented or disrupted performance of the work. In some cases, extensions may be allowed in excess of actual weather-related days if the impact affected the progress of the project. For example, if a contractor is doing backfilling and compaction work and has four days of unseasonably heavy rain that renders the soil too wet for compaction for an additional eight days, the effect on the job is longer than the number of days of rain.

A contractual right for a time extension for weather-related delays is not automatic. Contract clauses usually identify specific requirements for giving notice if an extension of time is requested. In some instances, constructive notice has been sufficient. Whatever the requirements, timely notice must be given to the owner.

In the event of an excusable weather delay, the owner must grant a time extension, permitting the contractor to complete the work later than the originally scheduled date of completion. The owner may not assess liquidated damages, may not terminate the contractor for default, and may not accelerate the schedule to adhere to the original schedule without additional compensation for an excusable weather delay. Additionally, excusable delays are usually not compensable to the contractor, and recovery from the owner of additional costs incurred may not be possible. If an owner-caused problem, however, shifts the contractor’s work into a season of unfavorable weather that becomes the proximate cause of the delay, it may become a compensable delay, and the additional costs of work can be recovered.

Proving that the weather was unusually severe can be problematic. Generally, weather bureau statistics over a five- to ten-year period are relied on to show normal weather conditions. In most cases, averages are inappropriate. Instead, the question should be: “What specific effect did the weather have on the work?” For example, if the contractor cannot work in temperatures below freezing, proof that the average temperature during a certain month was 10 degrees colder than usual does not show the effect of the weather. Detailed information must be presented showing the number of days normally below freezing during that month in previous years and the number of days below freezing during that month in the year in question. The difference is the proper number of days of excusable delay.

The government thoroughly explained this theory in denying a contractor’s claim for a time extension greater than that granted by the contracting officer.12 The contractor had proved, using weather bureau data, that the weather was more severe than normal but had submitted no proof of its impact on the work. Interestingly, the board permitted the contracting officer’s time extension to stand although it noted that it was theoretically improper since it was based on the “Lellis” formula—a guide to estimating the amount of delay that would result from severe weather (e.g., 0.10 inches to 2 inches of rain results in one day of delay; 2 inches results in a 1½-day delay).

The application of these principles indicates that no time extension for excusable delay will be granted to a contractor who cannot clearly demonstrate that the delay it encountered was directly caused by unusually severe weather. The mere proof of delay does not pass the test. Conversely, when the sequence of weather or a combination of factors produces unusually detrimental conditions, a contractor should be granted a time extension if it shows that the weather created an unusual delay, even though the weather was not statistically unusual. In summary, the key to this type of excusable delay is the use of detailed weather data to show the “specific effect” on the project.

If a contractor does not want to take the risk of weather delays, it should put contingency in its bid for field and home office overhead for weather delays and increased direct costs for lower labor and equipment productivity. Obviously, these additional costs need to be weighed in terms of the competitive nature of a contractor’s price.

1 Constructura Pan-Caribe, S.A., ENGBCA No. PCC-18, 73-2 BCA (CCH) ¶ 10,238 (1973); Appeal of Ray W. Lynch, IBCA No. 764-2-69, 69-2 BCA (CCH) ¶ 8026 (1969).

2 Canon Construction Corporation, ASBCA No. 16142, 72-1 BCA (CCH) ¶ 9,404 (1972).

3 Wilmington Shipyard, ENGBCA No. 3378, 73-2 BCA (CCH) ¶ 10,040 (1973).

4 Ford Constr. Co., Inc., AGBCA No. 241, 72-1 BCA (CCH) ¶ 9275 (1972).

5 Carlo Bianchi & Co., ENGBCA No. 3243, 73-2 BCA (CCH) ¶ 10,239 (1973); Pathman Constr. Co., ASBCA No. 14285, 71-1 BCA (CCH) ¶ 8905 (1971).

6 Roy L. Matchett, IBCA No. 826-2-70, 71-1 BCA (CCH) ¶ 8722 (1971).

7 Chris Berg, Inc. v. United States, 404 F.2d 364 (Ct. Cl. 1968).

8 Lucerne Constr. Corp., VACAB No. 1494, 82-2 BC.A (CCH) ¶ 16,101 (1982).

9 T. C. Bateson Constr. Co., GSBCA 2656, 68-2 BCA ¶ 7,263 (1968).

10 B.D. Click Co., ASBCA 24586, 84-3 BCA (CCH) ¶ 17,542 (1984); Constructura Pan-Caribe, S.A., ENGBCA No. PCC-18, 73-2 BCA (CCH) ¶ 10,238 (1973); Jonathan Woodner Co., ASBCA No. 4113, 59-1 BCA (CCH) ¶ 2120 (1959).

11 Constructura Pan-Caribe, S.A., ENGBCA No. PCC-18, 73-2 BCA (CCH) ¶ 10,238 (1973).

12 Essential Constr. Co., ASBCA No. 18491, 78-2 BCA (CCH) ¶ 13,314 (1978).

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Blog

Discover industry insights on construction disputes and claims, project management, risk analysis, and more.

MORE

Articles

Articles by our engineering and construction claims experts cover topics ranging from acceleration to why claims occur.

MORE

Publications

We are committed to sharing industry knowledge through publication of our books and presentations.

MORE

RECOMMENDED READS

Acts of God/Weather

Delays resulting from acts of God are normally excusable but noncompensable events in the absence of a contract clause stating otherwise.

READ

Force Majeure Delay Claim during the Construction of a New Hospital

This blog post explains how a contractor successfully mitigated a schedule and resolved an insurance claim after an extreme weather event.

READ

Types of Delay

Delays in construction contracts are usually categorized as one of three types. This post defines each type, with examples.

READ